In This Mountain Read online

Page 35

Of course he shouldn’t have brought Barnabas, it had been a foolish, last-minute notion and a desire for company. Now here he was, dirtying people’s bowls. He was mildly disgusted with himself. Retirement, of course, was the culprit. Unless one kept one’s hand in, things seemed to slide downhill.

Barnabas drank with great thirst and crashed onto the sitting room floor for a nap.

Five-thirty. Why didn’t someone come for him? And there was the smell again. What was it about that smell? Though faint, it repulsed him. He flexed his right hand, feeling the stiffness from gripping the car handle.

He paced the room, anxious, before realizing what he needed.

He needed prayer.

Dropping to his knees by a striped wing chair, he crossed himself. “Almighty and eternal God,” he prayed aloud, “so draw our hearts to Thee, so guide our minds, so fill our imaginations, so control our wills, that we may be wholly Thine, utterly dedicated unto Thee; and then use us, we pray Thee, as Thou wilt, and always to Thy glory and the welfare of Thy people, through our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.”

There. Better! Much better. He rose and peered through the window, where he saw only a bank covered with rhododendron. Where was the lake for this so-called lakeside service? Five thirty-two.

He turned, startled by his dog’s deep growl.

“Good afternoon, Father.”

Ed Coffey closed the door to the sitting room and looked at him, unsmiling. “Making yourself at home, I see.”

His heart pounded into his throat. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m just checking this door,” said Ed. He heard the lock click, and Barnabas barking on the other side.

“No!” he shouted, racing across the room. “Wait!”

Ed Coffey stepped quickly through an adjoining door as Edith Mallory stepped in.

“Timothy!” she said, closing the door behind her. “How good of you to come.”

He stood rooted to the spot, his breath short. “What do you mean by this?”

She smiled. “I paid a generous sum for you to come here. Therefore, I’m entitled to your company.” She shrugged. “That’s all.”

She walked across the room and sat on the love seat by the window. “Do sit down, Timothy.”

“I will do no such thing.” He went to the sitting room door and jiggled the knob.

“Barnabas! Are you there?” Silence. He turned quickly to the other door, frantic.

“It’s locked, Timothy.” Edith lifted the lid of a box next to the love seat and withdrew one of the long, dark Tiparillos she was known to smoke. She held it between her fingers before lighting it. “Ed will open it just after six-thirty. I’ve bought an hour of your time and I expect to have an hour of your time.”

She smiled in a manner he’d always thought ghastly.

“Consider me your congregation,” she said.

“Is Barnabas still in the other room?”

“Of course not. You’re far too courteous to disturb your congregation with the barking of a dog.”

“Edith, believe me, believe me…” He would throttle her with his own hands, he would.

“Believe you in what way?” She flicked a silver lighter. The end of her Tiparillo glowed; she inhaled deeply.

There! That was the sickly sweet smell he hadn’t been able to identify.

“If anything at all happens to my dog, I shall take every measure under heaven to see you brought down.”

“Umm,” she said, smiling again. “You’re far more attractive when you’re angry; I always thought so.”

“You are a wicked and unkind woman, Edith.”

“You’ve said worse about me in the past.”

“Everything I’ve ever said about you I’ve said to your face.”

“Speaking of my face, you may notice that I’ve had a little…touch-up here and there. Do you like it?”

“No cosmetic procedure is capable of disguising a cruel spirit.”

“Oh, please. You’re in your usual high-and-mighty clerical mode, I see. Look around you, Timothy. Do you like this house? I bought it recently, already furnished with exquisite antiques. And what do you think of this rug? It’s Aubusson, of course, early Federal period. I know how you love beautiful things, it’s a shame you’ve never been able to afford them. All this might have been yours, once, along with many other comforts I’m able to offer. But you fancied yourself too proud. You know what is said about pride, of course.”

She patted the cushion beside her. “Come, Timothy. Come preach to me and save my soul.”

“I cannot save your soul. That is strictly the business of the Holy Spirit.”

“Then come and pray for me, dear Timothy.”

“Don’t taunt me, Edith. And don’t blaspheme God with your insincere remarks.”

“But I’m not at all insincere, I mean it truly. You’ve never prayed for me, just the two of us. I’ve always had to share you with hordes of people. You went ’round to everyone but me, Timothy, for more than sixteen years.” She made a pout and looked at him with the large, gold eyes he’d always likened to those of a lynx painted on velvet.

Since Pat Mallory died, she had done everything in her power to seduce and harass him; he would never have dreamed of praying with her alone. “I’ve often prayed for you, Edith. And often I had no desire at all to do it.”

“Do you think God answers prayer that isn’t prayed sincerely?”

“It was prayed sincerely. For years I’ve prayed you might turn from your coldness of heart and hurtful indiscretions, and surrender your life to Him. I don’t have to feel warm and fuzzy to pray that prayer for you, I pray it with my will alone, in accordance with the will of God that you abandon your soul to the One Who created you, the One Who died for you, and the only One Who is capable of truly loving you.”

She inhaled and let the smoke out slowly. “I’ve always found it hard to believe that God would love someone who doesn’t love Him.”

“That’s the way humans think. God is different. He loves us no matter what.”

“Timothy, there’s no way you’ll get me to believe that. Ever.”

“You’re right. There’s no way I can get you to believe that. The Holy Spirit, however, can get you to believe that, if He so chooses.”

He walked across the room to her. “Now tell me. What exactly is the nature of this charade?” He stood at the love seat, cold with anger. “Why are you holding me in a locked room? What are your intentions?” He swallowed down the fear. He could always break through a window….

“My intentions? I was forced to give away an additional twenty-five thousand dollars to keep the U.S. Treasury from being miffed with me. I called you in hopes we could come up with a plan, but you hung up on me.

“When you did that, I thought, how delicious to give money away and have some fun doing it! It’s quite a compliment, Timothy. I could have offered the hospital a piddling five thousand and given the remainder elsewhere. You would have come, of course, for a piddling five thousand. Shame on you, that’s why you’ll never amount to anything when it comes down to it. You should thank heaven for your wife, who amounts to so much more in the world’s view.” She looked at him through narrowed eyes and inhaled again.

“By the way,” she said, “if you tell anyone the room was locked, I shall deny it and say you made improper advances toward me.”

“What would you have me do, Edith?” He could not commit murder. He could not and would not. But he relished the thought for the briefest moment. His mouth tasted of bile.

“I’d have you deliver what you were paid to deliver.”

“A sermon? A full liturgy?”

“For twenty-five thousand dollars, Timothy, I should think a full liturgy would be in order. Wouldn’t you?”

“There are two problems with that. One is that I have no communion set with which to administer the Holy Eucharist. The other is that something crucial is required of the soul who presents himself to the Host. You must

be earnestly willing to repent of your sins.”

She threw up her hands in mock helplessness. “Then it’s simple. We skip the communion! I must say, you look charming in that stole. Isn’t it the one Pat and I gave you years ago?”

“It is not.”

“Well, then, do begin.” She drew another Tiparillo from the box and flicked the lighter. The tip glowed as she inhaled.

He stood dumbstruck, praying the prayer that never failed. What did God want of him in this thing? What could He possibly have intended by bringing him face-to-face with Edith Mallory in a locked room? It was a dream, a nightmare.

His knees, he realized, had begun to shake. He sat down at once in the armchair next to the love seat.

“I’ll give you your hour, Edith. Happily. There’s a little girl at the hospital right now, four years old, I think—her leg was broken by her uncle because she tried to run away from his abuse. Another child was born with a hole in his heart and is facing his third medical procedure. I could go on. The point is, if such an hour as this can spare these children even a moment of suffering—”

“You gag me, Timothy, with your preacher talk. Will you never weary of such pap?”

“Never.”

“You’re not alone, you know, in wanting to serve God. I want to serve God, too.”

“Yes, of course, but only in an advisory capacity.”

She furrowed her brow. “What do you mean?”

“Never mind.”

“You’re rude. You were always rude to me, Timothy. I find no excuse for it. Nor would God.” She pouted again, drawing her mouth down at the corners.

“Would you care to put your cigarette out?”

“I wouldn’t care to.”

He stood. “Let us begin.” His knees trembled, still. “Blessed be God; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

He waited for her response. “Will you respond?”

“And blessed be His kingdom,” she said, snappish, “now and forever. Amen.”

“Almighty God, to You all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid….” He didn’t know how he could get through this; it was a travesty. All he wanted was for God to get him out of this preposterous mess. He sat down again, humbled and desperate, without any poise left in him.

“Give me a moment,” he said. The message of the morning service, which seemed days in the past, suddenly came to him with the complete conviction with which he’d preached it. In everything…

“Oh, forget that stuff you learned from a book! I never wanted you to do a full liturgy, anyway, I could never remember all those tiresome responses. All I wanted is for you to talk to me, Timothy, to…to hold me.”

She leaned forward on the love seat. “You’re a human being, you have feeling and passion like everyone else. Are you so frightened of your passion, Timothy?”

As she placed her hand on his knee, he recoiled visibly, but didn’t get up and move away. Instead, fighting down the nausea, he thanked God for putting him in this room, at this time, for whatever reason He might have.

Be with me, Lord, forsake me not. I’m going to fly into the face of this thing.

He removed her hand from his knee and took it in his. He was trembling inside as he did it, but his hand was steady, without the palsy of fear.

“Let’s begin by doing what you asked. Let me pray for you, Edith.” Her hand felt small and cold in his, like the claw of a bird, the palm surprisingly callous. He felt her flinch, but she didn’t withdraw her hand—the beating of her pulse throbbed against his own.

He bowed his head. “Father.”

But he could do no more than call His name. “Abba!” he whispered. Help me!

Christ went up into the mountain; He opened His mouth and taught them…But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you….

“Bless your child Edith with the reality of your Presence,” he prayed, and was suddenly mute again.

He was forcing himself to intercede for her; it was stop and start, like a mule pulling a sled through deep mire. He quit striving, then, and gave himself up; he could not haul the weight of this thing alone.

“By the power of Your Holy Spirit, so move in her heart and her life that she cannot ignore or turn away from Your love for her. Go, Lord, into that black night where no belief dwells, where no candle burns, where no solace can be found, and kindle Your love in Edith Mallory in a mighty and victorious way.

“Pour out Your love upon her, Lord, love that no human being can or will ever be able to give, pour it out upon her with such tenderness that she cannot turn away, with such mercy that she cannot deny Your grace.

“Fill her heart with certainty—with the confidence and certainty that You made Edith Mallory for Yourself, that You might take delight in her life…and in her service. Yes, thank You, Lord, for the countless thousands of dollars she’s poured into the work of Your kingdom, for whatever reasons she may have had.” Right or wrong, a good deal of Edith Mallory’s money had counted for good over the years, and he would not be her judge.

He was gripping her hand now; as he had gripped the handle above the passenger door, he was holding on to her as if she might be taken from him by force.

“Thank you, Father, for this extraordinary time in Your presence, for holding us captive in the circle of Your love and Your grace. With all my heart, I petition You for the soul of this woman, that she might be called to repent and become Your child for all eternity.”

Beads of sweat had broken out on his forehead, though the room was cool.

“Through Christ our Lord,” he whispered. “Amen.”

He raised his head slowly, feeling an enormous relief.

Tears had left a smear of mascara on her face; she withdrew her hand from his. “I despise you,” she said. “I despise you utterly.”

“Why?”

“Because you believe.”

She took a handkerchief from her suit pocket and pressed it against her eyes. “I think for the first time I actually believe that you believe.”

“Why do you despise me for that?”

“Because I would like to believe, and cannot.”

“Why can you not?”

“Because none of it makes sense to me.”

“Good!” he said.

“What do you mean, good?”

“Faith isn’t about making sense. Faith is faith.”

“Foolishness!” she said.

“Chesterton put it far better. He said, ‘Faith means believing the unbelievable, or it is no virtue at all.’”

“Enough of such blather! I don’t know why I did this ridiculous thing.” She tapped the ashes from her Tiparillo, impatient.

“Who are you, Edith? I met you nearly twenty years ago, yet I know almost nothing about you. Who were your parents? What was your life like when—”

Her laughter was hoarse. “I’ve never paid twenty-five thousand dollars an hour to be analyzed, especially by a country priest, and I don’t intend to start now. I’m sure you learned a great deal about me from my husband, though he was devoted to twisting the truth. He loved saying how he frequented that grease pit you call the Grill, in order to be out of my presence.”

He’d known as much. Pat Mallory often spoke maliciously of his wife.

“I cared nothing for my husband because I quickly learned he could be beaten down. A man who can be beaten down is no man at all. That’s one reason I’ve been intrigued by you over the years, Timothy—it’s difficult to beat you down.”

“If God be for me, who can be against me?”

She stiffened. “Can’t you have a simple conversation without dragging God into it? I abhor piety. It’s something clergy in particular should strive to avoid.”

“This is going nowhere.”

“Perhaps you’d be titillated by a bit of local Mitford gossip. I’m selling Clear Day. I always hated Mitford, Mitford was Pat’s idea. All

of you think yourselves above me, I’ve scarcely received a decent welcome there in years.” She angrily stubbed her Tiparillo in an ashtray.

“You tried to rig a mayoral election, you tried to throw a family out of their rightful lease—”

“I’m sick of this nonsense. Go home!” She rose from the love seat, so near to him that he couldn’t get up from the chair. “In the end, what misery it always brings to be in your company. It wasn’t worth it, not twenty-five thousand, not twenty, not five.”

She strode to the door, where she turned, her expression pained and bitter. “Your hour is up. Collect your dog outside.”

“Edith.”

Her hand was on the knob “What?”

“I have a request.”

She looked at him, frozen.

“Tell Mary Fisher I’d like to drive the car to the parking lot. If this isn’t agreeable, I’ll walk down.”

She burst suddenly into laughter. Still laughing, she opened the door, then slammed it behind her.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

Salmon Roulade

“Father Tim?”

“Yes!”

“I’m sorry to call you so early, this is Jeanine Stroup at th’ hospital, I’m new and don’t know everybody yet. Mr. Bill Watson’s askin’ for th’ preacher. Would you by any chance be th’ one, somebody said it was probably you.”

“Yes, ma’am, I think it’s probably me. Has he taken a bad turn?”

“Nossir, he’s pretty lively.”

“Wonderful! Well, look…how about eight o’clock?”

“Oh, good! I’ll go down the hall right now and tell him.”

“Can he have a doughnut?”

“A doughnut? I don’t know.”

“Plain, of course,” he said. “No jelly.”

“Why don’t you bring one, and if he can’t have it, I’ll eat it.”

“Jeanine,” he said, “I think you’ll go far.”

“Emma! Tim Kavanagh.” He didn’t have to apologize for calling; Emma got up so early, it was hard to beat her out of bed. “Got a minute?”

“Shoot.”

“I need some jokes off the Internet.”

“Jokes off the Internet? You, who don’t want anything to do with the Internet, absolutely, positively leave you alone about the Internet, you want jokes off the Internet?”

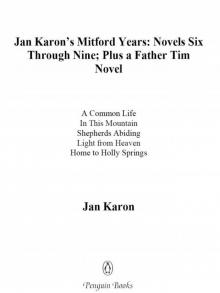

A Light in the Window

A Light in the Window Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good

Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good In This Mountain

In This Mountain In the Company of Others

In the Company of Others Come Rain or Come Shine

Come Rain or Come Shine To Be Where You Are

To Be Where You Are These High, Green Hills

These High, Green Hills Light From Heaven

Light From Heaven A New Song

A New Song Home to Holly Springs

Home to Holly Springs The Mitford Bedside Companion

The Mitford Bedside Companion At Home in Mitford

At Home in Mitford Shepherds Abiding

Shepherds Abiding Out to Canaan

Out to Canaan A Common Life: The Wedding Story

A Common Life: The Wedding Story Jan Karon's Mitford Years

Jan Karon's Mitford Years