A Light in the Window Read online

Page 31

"I have everything you have."

Bookends, he wanted to say, but didn't.

"Everything, that is, except a sinus infection, thanks be to God."

"There is a balm in Gilead."

"I'm making soup with the ounce of energy I got from eating a cracker," she said. "May I send some over?"

"Wonderful! I told Puny not to come in 'til the germs die down, so we're pushing along on our own over here. What time do you want Dooley to make a pickup?"

"Around five," she said, "and I'll leave out the carrots so he'll eat it. Now, with or without a cream base?"

"Without," he said.

"With or without a thin, golden-crusted little morsel of cornbread hot from the oven?"

"With!" he exclaimed, not feeling angry anymore.

Edith Mallory wanted him crawling on his hands and knees. All he was prepared to do, however, was call her again—just as soon as he went to the drugstore for Dooley's prescription.

Dooley had eaten a vast bowl of Cynthia's soup, cleaned up his share of the cornbread, crumbs and all, and fallen on the sofa, unable to move.

"You've done worked me to death," he said, his teeth chattering from the chill that raced through him.

"Tit for tat," replied the rector, covering him with the afghan.

"Timothy, I am not a charity organization." Edith's brown cigarette lay smoldering in the ashtray on the table.

"That's not what I'm saying, Edith."

"Priests are so idealistic—they're like children, really. They know nothing about business."

"I do realize your need to make investments lucrative, to be a wise steward of what you..."

"Then do stop nagging me to do what you're asking. A twentypercent rent increase is not worth bothering about." She stirred sweetener into a glass of tea, while lunch progressed into his digestive system like so much gall.

"The mayor has done everything in her power to stop progress in this town, and while you may think those tacky shops on Main Street are charming, they're an economic liability of the worst sort. Look at that hideous awning on the Grill and that peeling paint."

"May I remind you that hideous awnings and peeling paint are a responsibility of the property owner and not the tenant?"

"Don't mince my words. A fine dress shop from Florida, where people know how to do, Timothy, will bring in more shops like it. It will raise rents all along the street. It will..."

"It will destroy the character it has taken more than half a century to create. It will erase something central to the core and spirit of the town and demolish a sense of connectedness that is disappearing throughout the country—something we're desperately longing to return to, though in most places it's far too late..."

"Oh, for heaven's sake," she said, "stop preaching to me. Save that for the pulpit! I always knew you were oldfashioned, but I never dreamed you were so set in your ways."

"That may be. I'm also saying that doubling the rent is unfair and is clearly a strategy to get the Grill off the street. Another thing. How carefully have you considered the cost of leasing this space to a fine dress shop and the amount of upfitting they'll require of the owner?"

"It has all been considered, and it is all decided. Unless your people can pay the rent I'm asking, which is perfectly legitimate for Main Street, the dress shop will occupy the property on May 16. And no, I can't wait until your people find a new location, if there is such a thing, because the shop owners must occupy on the sixteenth or go elsewhere. Believe me, I'm going to see they don't go elsewhere."

"Waiter," he said, "would you bring the check?"

She crushed out her cigarette. "And don't expect me to pay it, like so many clergy do."

There was one thing he could say for her, but only one:

She hadn't strung him along.

Percy had better be ready to pack up and not look back.

He couldn't separate the anger from the sorrow. "Vent your anger," the bishop had said a few times, "or it turns into depression—then you're down in the mire with half your parish."

He didn't feel up to racing his motor scooter out to Absalom Greer's country store, though the weather was certainly good for it. He was not yet well enough to jog, and smashing glasses into the fireplace was too theatrical.

Instead, he put on a pot of soup, gave Dooley his medicine, read to him from a veterinary book, and brushed Barnabas. Then, while the soup boiled over on the stove, he fell asleep on the sofa, exhausted.

"Are you well, Cousin?" she called through the threeinch opening. He let out a racking cough and shoved his handkerchief to his face. Then he blew his nose as loudly as he could. She shut the door. There, he thought That ought to hold her for another day or two.

"She's set on it, Percy. I did my best."

Percy looked thinner, and there were dark circles under his eyes. "Thank you, Father. I know you did. I ain't worried about it."

"Percy's cookin' is starting to reflect his mood," said J.C. "Lookit this sausage." To make his point, he tried to puncture it with a knife, only to have it skid across his plate.

Mule scowled at Percy. "You got to keep up, buddyroe. You can't let down, especially not here at th' last."

"Depression," said J.C. "That's what it is. That and denial."

"Depression comes from anger," said the rector. "You need to let off steam."

"We could all go to Wesley and get drunk," said Mule.

"Fine," said J.C, "except nobody drinks—besides th' father, that is,

who knocks back a little sherry now and then."

"I forgot," said Mule, "that J.C. goes to A.A., I don't drink anything stronger than well water, and Percy was raised Baptist and never touched a drop."

J.C. raked the last of the buttered grits onto his toast. "Bein' raised Baptist can drive you to drink, if you want my opinion."

"So how could Percy let off some steam?" asked the rector. "We need to brainstorm this."

"I'll tell you how," said J.C. "Let Omer Cunningham fly you around in that old airplane, upside down and backwards. That'll do it. You'll be so glad to get on th' ground, they could take this place and turn it into a hubcap museum, for all you care."

"Let Fancy give you a face mask," said Mule. "No charge. On the house."

"A what?" asked Percy, looking done in.

"A face mask. It cleans out your pores."

Percy got up and went to the men's room.

"We're makin' him sick," said J.C.

"We've only got eight days to the fifteenth." The rector took off his glasses and rubbed his eyes. "So, what's the answer?"

"There isn't one," said Mule, sounding oddly philosophical.

He had never seen Dooley Barlowe look so haggard and pale. He opened a can of ginger ale and went upstairs and sat on the side of his bed.

"I got you another week of KitKats," he said, holding up the bag. "Thanks for using them as we agreed."

"One every other day, and no cheating," said Dooley, looking feverish. "Leave 'em in here or that woman'll git 'em."

The rector pushed the bag under the bed. "There. Completely out of sight. So how are you feeling?"

"I'd as soon be dead."

"I know the feeling. We'll have a talk when you're better."

"Who's lookin' after ol' Cynthia?"

"I am. The torch has passed to me."

"How's she doin'?"

"Still a bit down."

"Are you goin' to marry her?"

"Well..." he said, as if the wind had been knocked out of him.

"Are you or ain't you? I would, if I was you."

"You're not me."

"I'm dern glad of that."

"Why are you glad of that?"

"You ain't no fun."

"Aren't no fun. Come to think of it, you're not exactly a million laughs, yourself. Why would you marry Cynthia if you were me?"

"Because she's neat. She's fun."

"What's so fun about her?"

"She picked 'at ol' mouse up

by th' ear and th'ow'd it at me when I laughed at 'er."

"Throwing around a dead mouse is fun?"

"It is if you don't have nothin' else to do," said Dooley.

Dooley's flu hung on longer than his own had done, but then, he had pushed himself, Cynthia was still moping around in her bathrobe and curlers, with scarcely enough energy to bring in the mail.

"It's all right to take your time getting well," he said, having a cup of tea in her workroom. "You've worn yourself out on the book. Allow time to rest. Don't push yourself." He had never been able to take his own advice.

He picked flowers and left them on her kitchen cabinet and brought her a book of quotations from Happy Endings. He stopped by Winnie Ivey's for a napoleon, which he was tempted to step into the bushes and devour on the way home, but delivered it straight to her door.

He sat and read to her one evening while she put her feet on the ottoman and looked pale, and he also endured her infernal sighing.

He even opened some foulsmelling concoction and fed it to Violet, who scratched him on the ankle for his trouble.

If this was what marriage was like, he thought, he was getting a good dose. Cynthia Coppersmith was lapping up his doting attention like cream, without so much as bothering to take the curlers out of her hair.

"That woman left!" Dooley yelled from his bedroom. He walked to the boy's doorway and looked in. "Left? When?"

"After you went to your office. I seen 'er creepin' down th' stairs." He went to the guest room door and tried the knob. Locked. "She'll be back," he told Dooley. "Poop."

"Tomorrow night is when we'll talk. You'll be well enough and in the nick of time, too. You start back to school on Monday." Dooley pulled the covers over his head.

"Well! I see you went out. That's good news."

"I went out for personal items," she said, ducking through the kitchen in her trench coat.

"I love you," he would say, meaning it.

"That's the first thing I want you to know."

Then, he would talk about school laws and how they're designed for the common good, not to mention individual good, which, in this case, had everything to do with health.

Then, he would deal with the issue of wrong friends and once again go over the ramifications of stealing as it affected personal character and spiritual freedom.

He would close with the warning Buck Leeper had commanded him to pass along. Here was yet another infraction of rules, another instance of disregard for set boundaries. He would not allow this sort of behavior to become a pattern, and neither did he want to make any threats he couldn't keep.

He pondered what Dooley liked best:

Playing with Tommy, singing in the chorus, listening to his jam box, eating hamburgers.

To underscore the tenday suspension, he could remove everything but the chorus—but should he remove them all at once or in descending order? And for how long? He would call Marge Owen, who had raised two and was sufficiently skilled to be doing it all over again.

This was treacherous ground, and for Dooley's sake, he didn't want to step in a hole.

To accommodate two working mothers, the ECW changed their morning meeting to an evening meeting but failed to tell him. As he was the speaker, along with Mayor Cunningham and a Wesley town official, he had to change his own plans and be there.

"We'll talk when I come home." he told Dooley, who was well enough to watch TV But when he came home, the boy was in bed, snoring, his red hair lying wetly on his forehead.

He looked down at his freckled face and the arm thrown over the covers, grateful for all he had brought into the silent rectory, including the worry and aggravation.

Barnabas, who was sleeping at the foot of Dooley's bed, didn't raise his head but opened one eye.

Right there was some of the best medicine Dooley Barlowe had ever had. His dog could positively cure what ailed you—not to mention the fact that he was an upstanding churchgoer into the bargain.

He looked out his alcove window before getting undressed and gave his neighbor a quick call.

"Hey," he said when she answered the phone.

"Hey, yourself."

"What's going on next door? Do I see your Christmas lights burning?"

"I'm celebrating. "

"Alone?"

"I wouldn't be, if you'd come over."

"Well...," he said, uncertain.

"No strings attached."

That was fair enough. He went over.

She invited him to sit on the love seat in her workroom.

"What are you celebrating?" It must be fairly momentous, as she had taken the curlers out of her hair and looked terrific.

"Being alive."

"You were that sick?"

"It has nothing to do with being sick. We breathe, we run around in our underwear, we go to the store, we dig up the tulip bulbs or plan to, we make soup and pay the electric bill, and we never stop to think— we're alive! This is a gift!

"I wasn't even pondering this. I wasn't being poetic or introspective. It's just that I glanced at the floor—right there—this afternoon and saw how the light came through the window and fell on the wood.

"It bowled me over. It took my breath away. I could hardly bear it."

He was silent, looking at her.

"There was so much life in the light on the wood, the way it folded itself gently into the grain. That little spot on the floor radiated with tenderness. And then it was gone."

He couldn't stop looking at her and didn't try.

"Do you know?" she asked softly.

"I know," he said.

"Not everyone knows," she said.

"Yes."

They heard the ticking of her clock in the hallway outside her workroom.

She was perched on the stool at her drawing board. "Why don't you come and sit here?" he said.

She slid off the stool and came to him and sat down, and he took her hand. They were quiet for a time, in a soft pool of light from the lamp.

It occurred to him that he wanted to kiss her, to hold her close, but he didn't deserve it. He didn't deserve even to be sitting here, a man who couldn't make up his mind from one hour to the next.

She leaned her head to one side, in that way of hers. "What are you thinking?"

"That I want to kiss you," he said. "More than anything."

She smiled. "No strings attached?"

"Yes," he said. "No strings attached."

He couldn't help it that Dooley had a mild relapse on Saturday night and that he didn't feel so good himself. Nor did he intend to fall asleep on Sunday after church and nap until the afternoon, which is when Dooley fell asleep and was out like a light until dinner-time. He meant to discuss the whole thing with him that night, before the boy went back to school the following morning, but when he sat on the side of Dooley's bed, it was all he could do to say, "Listen, this can't happen again. Do you hear me?"

Dooley had seemed to hear him, but he couldn't quite forgive himself that he hadn't handled it right. No, he hadn't handled it right at all.

The lilacs bloomed so furiously that not a few of the villagers turned out to view the bushes.

"You've got to walk down behind Lord's Chapel," Hessie Mayhew told Winnie Ivey. "There's a white bush you won't believe! Take a camera!"

"Come and look!" Cynthia called through the hedge one morning. Barnabas nearly pulled him down racing to her yard where an ancient purple bush, halfhidden by the garage, was massed with fragrant blooms.

Andrew Gregory invited two friends from Baltimore to "come for the lilacs" and took them up and down Main Street to meet everybody from the postmaster to Dora Pugh, whose window display at the hardware store had changed to seed packets, bonemeal, garden spades, and wooden trellises.

On Sunday, the rector felt a lightness of spirit like he'd seldom known.

He walked toward home, as if on air, until he saw Percy and Velma driving down Main Street after the Presbyterians let out.

Percy didn't

see him, but he saw Percy—and he was shocked at the grief so plainly revealed on his friend's unguarded face, as if it could no longer be hidden.

•CHAPTER SIXTEEN•

AND THE NAME OF THE SLOUGH WAS DESPOND," said J.C, who couldn't eat a bite.

Th' last supper," said Mule. "With its own Judas."

They had all seen the sign on the door.

LAST DAY

After lunch,

the Main Street

Grill will be

officially closed.

New location

to be announced.

Thank you for

your business.

J.C. stared into his coffee cup. "I helped pack last night. It was awful."

"I'll help tomorrow," said Mule, "and Fancy's comin' to help Velma.

Omer's loadin' this end. Lew Boyd's unloadin' the other end. We got four college kids from Wesley, and Coot and Ron are runnin' their trucks to the warehouse."

"Well done," said the rector. "I'll be here tomorrow at daylight."

J.C. rolled his eyes. "Good luck with what's down th' hatch."

"What's down there?"

"Fiftytwo years of bein' in the food business. You got creamed corn in cans big as this booth, not to mention stewed tomatoes and sauerkraut out th' kazoo. You got busted display cases, old counter stools, rusted tin signs, milk crates, and a jukebox that'll take four men to lift it. Did you know this place had a jukebox in 1950? His daddy was trying to loosen up and go after a new demographic. Percy won't throw away a bloomin' thing, so eat your Wheaties."

"You're not packin' tomorrow?" Mule wanted to know.

"I've got a paper to get out."

"How are you going to treat the story?" asked the rector.

"I'm blaring it across the whole front page. Big photo of the sign on the door. Headline says, Read It and Weep. We'll run a black border around the front page—which hasn't been done on the Muse since World War Two. What do you think?"

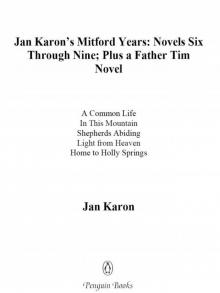

A Light in the Window

A Light in the Window Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good

Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good In This Mountain

In This Mountain In the Company of Others

In the Company of Others Come Rain or Come Shine

Come Rain or Come Shine To Be Where You Are

To Be Where You Are These High, Green Hills

These High, Green Hills Light From Heaven

Light From Heaven A New Song

A New Song Home to Holly Springs

Home to Holly Springs The Mitford Bedside Companion

The Mitford Bedside Companion At Home in Mitford

At Home in Mitford Shepherds Abiding

Shepherds Abiding Out to Canaan

Out to Canaan A Common Life: The Wedding Story

A Common Life: The Wedding Story Jan Karon's Mitford Years

Jan Karon's Mitford Years