Light From Heaven Read online

Page 27

Sammy loosened his arm and wrist with a couple of practice strokes of the cue, then stroked the ball, hard. In the empty room, the loud and sudden cracking sound was startling.

“Good grief! What did he just do?”

“Broke th’ rack.”

“I’m sorry, we’ll certainly replace it.”

Bud hooted with laughter. “Don’t worry, nothin’s busted.”

Father Tim adjusted his glasses. He was needing new lenses, big time, but he could see the look on Sammy’s face.

Sammy Barlowe liked shooting pool better than planting peas.

“He’s a slick little shooter,” said Bud. “Got a nice stroke.”

“I wouldn’t know, never shot pool.”

“You ought t’ try. Whoa, look at that.”

“What?”

“Put a little high left English on th’ cue ball an’ drove th’ three ball in th’ upper right corner. Th’ cue banked off three rails an’ dropped th’ seven in th’ lower right corner.”

“Aha.”

Sammy appeared completely focused, oblivious to anything except the table.

“Looks like he knows how to concentrate. Th’ problem with most shooters is, they cain’t keep their mind on th’ table.”

The cue ball cracked against the object ball and sent it into the upper right pocket.

“Pretty nice. How long’s ’e been shootin’?”

“A few years is my guess. At a place down in Holding.”

Bud leaned against the end of the bar, squinting toward Sammy’s table.

Sammy banked the four ball off the rail and put it in the side pocket. Then he hunkered his tall frame over the rail, and with his right hand made an open bridge for the cue stick. He studied the table intently and fired his shot.

“Blam!” said Bud. “Sonofagun.”

“That t-t-table ain’t no g-good,” Sammy told Bud.

“I don’t see it held you back any.”

“It m-must be settin’ on a slope.You ought t’ level it.”

“It don’t bother most people. But here’s your money back.”

Sammy looked annoyed. “Plus you got a couple of bad d-dimples in th’ s-slate.”

“You want t’ keep shootin’, that table on th’ left is as level as level can git.”

The door opened and four customers blew in, one carrying a leather case under his arm.

“There goes th’ neighborhood,” Bud told the vicar.

“Th’ kid in th’ blue jacket is Dunn Craw-ford, th’ vice chancellor’s boy. He’s a smart ass with a big mouth, an’ th’ only customer I’ve got that carries his own cue stick.”

Father Tim felt mildly uneasy. The new customers had somehow changed the way the room felt.

“Dunn’s buddies call ‘im Hook. He’s a hustier that goes after th’ country boys. Reels ’em in like fish.”

Father Tim watched Dunn light a cigarette and eye Sammy. Sammy never looked up. His cue ball cracked against the two ball but missed the mark.

“Rattled in the pocket,” said Bud.

Greek, thought the vicar. Croatian!

He and Bud watched Dunn watching Sammy, while the other three in Dunn’s crowd hassled about who had paid for the beer last time.

“I’ll lay you money ol’ Hook’s goin’ to hustle your boy.”

“Should I let Sammy know?”

“In life, you’re goin’ t’ git hustled, they ain’t no way around it. Maybe he’ll learn a good lesson. Th’ way I look at it, this game’s about a whole lot more than pool, that’s what keeps it in’ erestin’ .”

“All them boys is college-ruint.” Bud lit a cigarette, took a long drag, and exhaled through his nose.

Dunn had warmed up with a couple of games of partners’ eight ball, and walked over to Sammy’s table.

“Haven’t seen you in here before.You shoot pretty good.”

“Th-thanks,” said Sammy. “Not g-good enough t’ have m’own s-stick.”

“Birthday gift from my dad. I’m pretty lousy, really. Bet you could teach me some stuff.”

“Here it comes,” Bud said under his breath.

Dunn made a couple of random shots on Sammy’s table and missed both.

“Look, since I don’t have much time, let’s play best two out of three games of nine ball. For ...” Dunn lowered his voice.

Sammy shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“Come on.”

Sammy shrugged again. “OK, I guess.”

Dunn removed the striped balls, except for the nine, which he racked with the others. “Go ahead and break ’em up if you want to.”

Sammy lined up his break and stroked hard.

The balls careened around the table; the seven rolled in.

“Got to catch th’ phone,” said Bud. “You’re on your own.”

Father Tim climbed onto the stool and drank bottled water. Sammy’s scar was blazing as they finished the game.

“Who won?” he asked when Bud came back to the end of the bar.

“Your boy. That means he’ll break again.”

Sammy broke the rack.

“Pretty nice. Two balls on th’ break shot, an’ a good leave on th’ one ball. He’s makin’ a very soft stroke here, yeah, great, sinks th’ one. Okay, he’s got an easy shot at th’ five ball to th’ upper corner ...”

Sammy bent over the table, his chin just above the cue stick, and made his shot.

“Stroked th’ ball too hard,” said Bud. “Rattled in th’ pocket.”

Dunn’s buddies quit their own game, and walked across to the table on the left. Father Tim saw the look on their faces as they watched Sammy. Not friendly.

Dunn aimed at the five and put it away.

“Where ’is cue ball’s at don’t give ’im much of a shot at the six ball.” Bud ground out his cigarette and watched Dunn bend over the table. Dunn stroked the cue ball with reverse English off the rail, just behind the six ball.

“Oh, yeah! Caromed off th’ six ball into th’ nine, right in front of th’ side pocket. Boom. Game’s s over.”

“Hey, Bud!” yelled one of the players. “Four beers and a deck of Marlboros!”

“Who won?”

“Hook.”

The vicar took out his billfold. “I’ll have another bottle of water when you get to it. Make it a double.”

Dunn broke with a shot that drove the one, six, and seven balls into the pockets. He lined up the two ball, stroked, and put it in the side pocket.

“Pretty slick,” said Bud.

Dunn attempted to bank the three ball the length of the table, but missed.

Sammy had nothing between the cue ball and the three, but other balls blocked a direct shot to a pocket.

“Cheese gits bindin’ right here,” said Bud.

FatherTim figured he didn’t have to know the game to identify the feeling in the room. Tense.

Sammy aimed and stroked the cue ball using upper-right-hand English. The cue ball barely touched the three ball, then rolled off the cushion with an angle that drove it onto the nine ball. The nine rolled toward the corner pocket, glanced off the eight ball, and fell into the lower corner pocket.

“Done,” said Bud.

The vicar couldn’t tell much from the faces of the pool players, including Sammy’s.

“What happened?”

“Your boy whipped ol’ Hook.” Bud turned toward the bar so nobody could see the grin on his face.

“You want a little summer job, I’d like t’ talk to you,” Bud told Sammy.

“He has a job,” said the vicar. “He’s a very fine gardener.”

On the way home, he could feel it coming.

“I’d like t’ work f’r Bud.”

“How do you think you’d get there?”

Long silence. Looking straight ahead, Sammy finally answered. “You could take me.”

Father Tim restrained himself from out-and-out hilarity, and merely chuckled.

“I skinned t-twenty bucks off

’is butt.”

What Lon Burtie had told him about Sammy’s gambling in the Wesley pool hall had, until now, gone from Father Tim’s memory.

“I didn’t know gambling would be going on today, I’m pretty dumb about these things. You’re a fine player, Sammy; Bud says you’re a natural. It’d be great to see you play for the thrill of the game. Let the game itself be the payoff.”

“I like hustlin’. I like it even b-better when s-s-some smart ass thinks he’s hustlin’ m-me.”

“You have a good job with good pay. You don’t have to hustle to put food on the table or take care of your dad like you once did. Money always changes things. It looks to me like pool is a great game, and it deserves better than that.”

They drove in silence for a couple of miles. He’d better lay it out right now, not tomorrow, not next week when Sammy wanted to go to Wesley again.

“Here’s how it has to be. I’ll drive you to shoot a little pool now and again, but only on one condition: No gambling.”

They drove the rest of the way in silence.

“You should see him shoot pool. Blew everybody away. The owner offered him a job!” He wasn’t ready to share the rest of the story.

“Say what we will about their upbringing,” said Cynthia, “the young Barlowes have some amazing capabilities. Where is he?”

“In the garden, seeing if anything’s sprouting. Who showed up today?”

“Lily.”

“Thank goodness!”

“Violet is on the docket for tomorrow.”

“You know they say Violet sings as she works.”

Cynthia wrinkled her brow. “Continually, do you think?”

“Not sure.”

“I’ve got to move my easel, Timothy The kitchen is tourist season at the Acropolis; it’s the Mall of America! I can’t keep doing this, and yet—that’s where the north light comes in.”

“Shall we go home to Mitford?”

She rubbed her forehead. “Ugh, I’ve had a splitting headache all day”

“We can work it out,” he said. “We could have you back in your studio, with everything pretty much in place, in two days.”

“No, I’d rather find a way to do my work and let everyone else do theirs.”

“Remember our retreat? We could have it tomorrow—and try to figure something out.”

She smiled, cheered. “I’ll bring the picnic basket.”

“And I’ll bring the blanket,” he said.

When Violet arrived at eight o’clock, she wasn’t wearing her cowgirl outfit, but something that resembled, however vaguely, an Austrian dirndl.

“Why, look here! An Alpine milkmaid!”

“I got it at a yard sale for three dollars!” she said, twirling around to give the full effect. “I also yodel.”

“Yodel?”

She threw her head back and demonstrated. “Idaleetleodleladitee, yeodleladitee, yeodleladeeeee!”

“I’ll be darned!” he said, blushing. “Umm, please don’t do that in the house; my wife works in the kitchen.”

“No problem!” she said. “Did you hear me on th’ radio?”

“I didn’t. But give us a heads-up next time, and we’ll try to listen in. By the way, we have a cat named Violet. She’s around here somewhere.”

“I’m crazy about cats. Lily don’t like ’em; she sneezes her brains out. Shooee, what’s ’at smell?”

“Creosote. Wind blew down part of our chimney. We’re working on it. Do you have a family, Violet?”

“Oh, no, sir, I’m barren like in th’ Bible, an’ my sweet husband died when he was thirty-five.” She snapped her fingers. “Th’ Lord took ’im just like that. Heart attack. It run in ’is fam’ly.”

“I’m sorry.”

“I ain’t found nobody as sweet as Tommy O’ Grady ...”

“I’m sure.”

Violet’s face was bright with good humor. “But that’s not t’ say I ain’t tryin’!”

“What do you think ... so far?”

“I love that she wants to dry sheets on the line instead of in the dryer. But she is terribly vocal. When she was hanging the wash, it sounded exactly like she was ... yodeling.” Cynthia appeared puzzled. “But surely not.”

“Surely not.”

He noted that their milkmaid had stopped on the path from the clothesline to the porch, and was watching the guineas careen through the yard.

Father Tim’s grin was stretching halfway around his head as he watched Lloyd watch Violet watch the guineas. “Lloyd,” he said beneath his breath, “your eyes are out on stems.”

Lloyd turned a fierce shade of pink. “Way out,” he said, grinning back.

“It’s a whole other world in here!”

Cynthia peered at the canopy of interlacing tree branches above the farm track. Light and shadow dappled the track, which was still recognizable beneath the leaf mold.

He knew at once an infilling peace. “Wordsworthian!” he said, smitten. “A leafy glade! A vernal bower!”

At the foot of the bank to their left, the creek hurried on its journey to the New River.

Cynthia released a long breath. “I could sit down right here and be happy.”

He sneaked a glance at his watch. In an hour and a half, he would need to talk to his lawyer about the adoption papers.

“I saw that,” she said.

“Saw what?”

“You looked at your watch.”

“I did. Force of habit.”

“What a lovely little creek—why don’t we pitch our camp here? I’m too famished to explore before lunch. And look, darling, this gives us a wonderful view of the sheep paddock.”

Indeed, the view along the track opened out of the woods to the green meadow, with ewes and lambs grazing among the outcrop of rocks. Beyond the rocks, the fence line, and farther along, the rooftop of the farmhouse beneath a spreading oak.

Happy, he smoothed their intended place on the cushion of leaves and moss, and together they spread the quilt on a slope toward the creek.

She lay on the quilt and gazed up at the tracery of limbs against a blue sky. “Thank You, Lord!”

“Yes, thank You, Lord.”

As he sat beside her, she turned her head and looked at him, content. “Churchill said, ‘We’re always getting ready to live, but never living.’ We should have done this sooner.”

“True enough. And then there’s this one, by a good fellow named Henry Canby:

“ ‘Live deep instead of fast.’ ”

Birds called throughout the copse of trees. “When the brick dust gets too thick, let’s always remember to come here and do what Mr. Canby suggests.”

He unwrapped their sandwiches. “We can handle that.”

She picked something from the leaves. “A brown feather,” she said, examining it. “Someday I’d love to do a book about how things look under a microscope.What might we see if I made a slide of it?” She twirled the feather between her thumb and forefinger. “What bird dropped it, do you suppose?”

“It’s a chicken feather,” he said.

Early afternoon sun filtered through the leaves above; they were light and shadow beneath.

He lay on his back beside her. “So what are we going to do about your work space?”

“Lloyd says we haven’t seen anything yet, it’s really going to get messy on Monday morning—they’ve been tiptoeing around the inevitable. Then there’s Lily, of course, who must have the kitchen if she’s going to cook, so we’re looking at ... chaos, to put it plainly.”

“Sammy’s room gets good light. Maybe, somehow...”

“I can’t do that.”

“Can we move you into the smokehouse? It has a window.”

“Ugh. Lots of creepy crawlies in there, and spiders with legs as long as mine.”

“Del would have them out of there in no time flat.”

“No, sweetheart. Even with a window, too dark and confining.”

“Here’s a crazy thought...” he said

.

“I love your crazy thoughts.”

“The barn loft. The old hay doors open straight out to the north.”

“The barn?” She was quiet for a time, thoughtful. “I don’t know. But He knows. Could we pray about it?”

He took her hand.

“Father,” he said, observing St. Paul’s exhortation to be instant in prayer, “thank You for caring where Cynthia cultivates and expresses the wondrous gift You’ve given her. We’re stumped, but You’re not. Would You make it clear to us? We thank You in advance for Your wise and gracious guidance, and for Your boundless blessings in this life... for the trees above us, and the good earth beneath. For the people whose lives You intermingle with ours. For Sammy, who was lost and now is found. For Dooley, who’s coming home ...”

“And I thank You, Lord,” prayed his wife, “for my patient and thoughtful husband, a treasure I never dreamed I’d be given.”

He crossed himself. “In the name of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ...”

“Amen!” they said together.

“That feels better.”

“Thanks for the kind words to the Boss.”

She patted his hand; they listened for a while to the bleating of the lambs.

“I hope poor J.C. can step up to the plate, as you say; I’m sure he has all sorts of lovely feelings that need to get into general circulation.”

“Feelings. There’s the rub! It was all those scary feelings that held me back for so long. And then, standing at the wall that evening, I had the agonizing sense that I was losing you forever.”

“I was thinking of leaving Mitford.”

“What if I hadn’t thrown myself at your feet? We would have missed everything. We would have missed this.” The creek sang boldly; a junco called.

“Worse yet, we would have missed the sugar-free cherry tarts hidden under the tablecloth that we haven’t unpacked.”

“Aha!” he said, digging at once to the bottom of the basket.

Cynthia had trotted home to finish April and sketch May, and he’d stayed behind to check out what now appeared to be the track of long-ago hay wagons. He would take care of the papers before five.

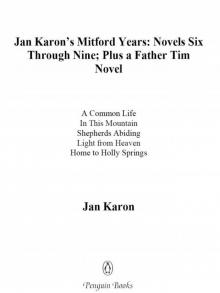

A Light in the Window

A Light in the Window Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good

Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good In This Mountain

In This Mountain In the Company of Others

In the Company of Others Come Rain or Come Shine

Come Rain or Come Shine To Be Where You Are

To Be Where You Are These High, Green Hills

These High, Green Hills Light From Heaven

Light From Heaven A New Song

A New Song Home to Holly Springs

Home to Holly Springs The Mitford Bedside Companion

The Mitford Bedside Companion At Home in Mitford

At Home in Mitford Shepherds Abiding

Shepherds Abiding Out to Canaan

Out to Canaan A Common Life: The Wedding Story

A Common Life: The Wedding Story Jan Karon's Mitford Years

Jan Karon's Mitford Years