Come Rain or Come Shine Read online

Page 11

‘I’m sendin’ Vanita out tomorrow to cover your big doings,’ said J.C.

‘No press,’ he said.

‘Come on. This is a big one. Everybody knows these kids, the whole town has been waiting for this wedding. Then there’s Dooley’s bull everybody’s talkin’ about. We’d like to get a shot of him, too.’

‘No press, J.C. It’s a small affair. Private.’

‘Be a sport, buddyroe.’

He seemed doomed to occupy the compressed space between a rock and a hard place. ‘That’s not for me to decide. It would have helped if you’d brought it up earlier. It’s a family wedding.’

‘Mitford is family,’ said J.C.

He felt like going home and digging up the bourbon himself.

June 13, 1:30 p.m.

Waiting for the call. My stomach is in a knot.

Tommy called to say the Biscuits would be out between two and three tomorrow and Beth and her mom will fly into Holding this evening and rent a car. Her mom will stay in Wesley, but Beth will bunk with me and be my handmaid, as she says. She is so good~ I will owe her big-time for coming when things are so crazy at her office.

Sammy is flying in tonight from Minneapolis, where he just finished a big tournament, and will bunk in the library with the pool table~ the love of his life.

Sometimes I forget to breathe.

Olivia says our wedding present will be a surprise. I feel guilty for hoping it’s a station wagon or hatchback~ my old Beemer is falling apart.

D truly loves me~ his love is more real to me every day. He says so a lot now. It’s not just me anymore going I love you I love you. I am so insecure sometimes. I think he is a little scared about everything~ it’s really enough to scare anybody. The wedding seemed super small when we started planning, but now it seems huge, even though it is the same number of people.

Tommy is so sweet and gifted~ and such a great friend to make the music happen for us. I wish he had somebody wonderful in his life. How do people find each other, Lord? I truly wonder. You put D and me in the same town with parents who are friends. That was easy, don’t you think? But it seems hard for other people.

Here is really what I sat down to write~

I have been worried about doing my part to ‘run’ this place, God. And just yesterday, I started to believe I can. But only with your help.

Waiting for the call is the hardest. I almost told Cynthia this morning.

I love my dress.

He was speeding. Not a good plan.

The call had come from Dooley around two-thirty. Short, not much info, though what info there was was big. Very big. His heart did an A-fib number.

No surprise could be more disarming, no grace more benevolent.

Jack Tyler was wearing a dark blue suit too large for his frame, with a dingy dress shirt and beat-up gym shoes. He carried his sole possessions in a black plastic bag with a tie—it appeared pretty empty—and held on tight to a stuffed kangaroo.

He had made it clear to the person who picked him up that he had to be called by his entire name. When people called him Jack, he felt like he was only half of himself, though he couldn’t have explained this feeling.

He also let the person know that he hated this stupid suit. He had never worn such a thing before, it felt like a trap. He had begged to wear his jeans and favorite T-shirt but his granny made him wear this mess.

‘That is a church suit from a church sale,’ said his granny. ‘They’re church people over there. You need to make a good impression so they’ll keep you around.’

He had lived with his granny in a trailer since he was a baby, and now he was four. There had been room in the yard for his trike and her truck and that was it. There had been a sandbox, but somebody had backed over it with a dirt bike. If he rode his trike across a line that he could not see but that his granny talked about all the time, the dog next door went ballistic and he ran in the trailer and hid in the bathroom and shivered all over.

‘There’s a toy for you under the seat,’ said the person.

‘I don’t want a toy.’

‘’Cause you already have a toy, right?’

‘This is not a toy, okay?’ His kangaroo was his friend. Roo was more real than the person driving this smelly bad truck.

When they turned into the driveway, he got a sinking feeling like he was going to upchuck. The person got out of the truck and came around to help him down.

‘No,’ he said.

He jumped down with his sack, remembering what his granny said. ‘Maybe I’ll come see you now an’ again, but things is goin’ on in my life, so don’t look for me no time soon.’

‘I won’t,’ he said.

This yard was big, the house was big, and this was more people than he had generally seen together at one time except when Sam Tully went off to heaven and people cried.

He wanted to cry, it felt like a cry coming, but his granny had said, ‘Don’t cry, you are not a baby, look at me, you don’t see me cryin’. So he didn’t cry, but he did think of climbing back in the truck when he saw the dogs, four of them, all barking straight at him but lying down. He had never seen a barking dog lying down.

He moved close to the person who had gone too fast around the curves. He had not said anything about going too fast but had held on to his kangaroo. His granny went fast, so he was used to going fast, except with somebody he did not know it seemed faster.

‘There’s your mom and dad right there, comin’ out th’ door,’ said the person. ‘Aren’t they a pretty sight! We’re late as th’ dickens.

‘It was th’ log trucks!’ the person shouted.

The mom and the dad were coming straight at him and the mom was crying even though she looked happy. He had never had a dad and could not remember anything about his real mom except the scar on her arm and the smell of her shampoo and her laugh, which was really loud. He made his body stiff just in case.

The new mom squatted down to his size. ‘Hey, Jack Tyler,’ she said. He stepped back. She was pretty like on TV and smelled like cookies.

The new dad squatted down. ‘Welcome home, Jack Tyler.’

He could see straight into their eyes.

He hardly had any breath to ask the question. ‘Does those dogs go ballistic?’

‘Never,’ said the dad. ‘They are beyond ballistic.’

‘Does they bite?’

‘They don’t have enough teeth to bite,’ said the mom.

He thought of what his granny told him. ‘You’re jis’ bein’ fostered, you ain’t adopted yet, so you be good, you hear?’

He thought he was pretty good except when he hated his granny so hard that he shivered and couldn’t stop. He had run away once, but she caught him and took his kangaroo and throwed out the baby from the pouch. She had throwed it way out in the pond and he could not swim.

When he thought of that, he could not hold it back, so he cried now and they let him do it and they cried with him and the mom said it was okay.

He thought that maybe once in a while they could do it, anyway. ‘Does they ever sometimes bite?’

‘They don’t have no teeth to bite,’ said Harley. ‘Like me. Looky here.’ Harley made a toothless grin.

‘For th’ Lord’s sake!’ said Lily. ‘Stop that! You’ll scare ’im to death.’

He had never smelled so many good smells or seen so many people talking at the same time. On the table there was piles of cookies. Piles. He had never seen piles of cookies. And there was pies, too. A lot of pies.

‘How about a sandwich with your lemonade?’ said the mom.

No.

‘With chicken and tomato and lettuce and mayo?’

No. He did not like to eat around strange people.

She handed him a cookie. ‘It’s chocolate chip,’ she said. He thought her long hair was like on TV.

H

e took the cookie; it was still warm.

‘Hey, buddy.’

It was somebody who looked like the dad but was another person with red hair. ‘I’m Uncle Sammy.’ Uncle Sammy was really tall and stooping down and holding out his hand. He could not shake it because he was holding his cookie.

‘Welcome to th’ z-zoo. We’ll shoot us some pool after while,’ said Uncle Sammy. ‘Y-you okay with that?’ he asked the mom. ‘Abraham Lincoln shot pool, Mark Twain, President John Adams, V-Vanna White . . .’

She laughed. ‘If there’s time,’ she said.

He had seen people on TV shoot pool.

‘Who’s your buddy there?’

‘Roo.’

‘He’s losin’ his stuffin’. I used to lose my stuffin’ p-pretty regular.’ Uncle Sammy laughed, rubbed him on his head just after the mom had combed his hair. ‘Okay, Jack, be cool.’

‘It’s more than Jack,’ he said. ‘It’s Jack Tyler.’

‘Jack Tyler. G-got it. Goin’ out to see th’ cattle. Catch you later.’

He had drunk a whole glass of lemonade and besides, there were so many people he had to pee. He could not wait another minute and the dad was at the barn. ‘I have to go,’ he said to the mom.

‘Do you want to leave your kangaroo here?’

‘No,’ he said.

She took him by the hand and led him to what she called the hall room and shut the door and he stuffed the cookie into his mouth. He saw lights behind his eyes. He had never tasted such a good cookie. It was soft and chewy and the chocolate was runny and he had to wipe his hands on the towel.

He did what had to be done and zipped up his church pants and stood for a long time wondering when it would be okay to go back out with all those people who seemed glad to see him and what he should do to not disappoint them and keep getting cookies.

He picked up Roo, made his body stiff just in case, and opened the door.

‘Jack Tyler.’

He squatted before the boy, holding back the tears. What a holy amazement. ‘Welcome home. I’m Dooley’s dad, Father Tim.’ Maybe that was too much information.

‘What’s that white thing around your neck?’

‘My collar. I’m a priest.’ Definitely too much information. ‘Have you seen the cows?’

All the way home, he had wondered what to say to a four-year-old boy. It was a while since he’d been one.

The boy in the baggy suit was overwhelmed, as anyone would be. And he, the grown-up, had to search for words. They looked at each other for a long moment. They were both pleading for something, though he couldn’t say what. Perhaps the boy was pleading for someone to trust, and himself, a priest for a half century, pleading for a general forgiveness for not always knowing how to love. How he would get up from this squat was another matter.

‘Here’s a hug,’ he said to Jack Tyler, who came without pretense into his arms. He held him close, feeling some of the tension flow out of the boy, out of the man, and grace flow in.

He walked with Dooley to the truck parked behind the corncrib and they climbed in and left the doors open.

‘Two years ago, Lace and I went on a call with Hal. A pony with a bladder infection. There was a pond on the place, and when we drove out to the pony, we saw this little kid, maybe two years old, standing at the edge of the pond. He was squatting down and leaning over the water and we thought no way is this supposed to be happening. So Lace ran over to the little guy, he was in nothing but a diaper and it was plenty cold that morning. He said he was looking for something, so you can imagine where that was going.

‘It was Jack Tyler. We both fell in love with him. Turns out his dad was killed in a motorcycle accident and his mother was long gone. He was living with his maternal grandmother, not a good thing. No way. We reported what we’d seen, but she was able to talk around the incident and keep him. We think it helped get her straight, but we worried, he stayed on our minds.

‘We’d wanted to have kids when we got married. Four seemed to be the number. But we prayed about it and said, Look, let’s make it five, we need to get this little guy out of there.

‘I was two years away from graduating vet school, and the mother wouldn’t relinquish rights, so it didn’t look good. But we signed up anyway for fostering to adopt, and moved ahead, hoping.

‘He’s thoughtful and sensitive, Dad. You’re going to love him.’

‘Did this run through the court system?’

‘It’s a foster program by a home for kids like Jack Tyler. We did thirty hours of training, drove up on weekends to Meadowgate. There was a stack of homework, six sessions of five hours each with counselors, complete physicals—you name it, we did it, they totally worked us over. There were background checks and fingerprinting, plus house, fire, and environmental inspections.

‘Because Lily and Willie would continue to work here, they were also interviewed and background-checked and so were the clinic staff. It was a hassle for everybody, especially Hal and Marge, but they were committed. We had to tell everything about our backgrounds, really emotional stuff. We hated it, there were times we wanted to give up. But we loved Jack Tyler, even though we weren’t allowed to see him. We had to go on that one scenario by the pond.

‘So we got the license, and we’ve been waiting for the call, waiting for the mother to relinquish all rights. We didn’t know if that would happen, but it finally did. She gave him up, Dad.’

‘Completely?’

‘Completely. Living in California. Right now he’s legally an orphan. No legal ties to anybody, he belongs to the state. We have to wait a minimum of six months before we can adopt.’

It was a lot, to say the very least, to take in. ‘We’ll be there for you, every way we can.’

‘We wanted to tell you, but we didn’t know if it was going to happen. Forgive us for not telling you. I tried a couple of times early on, but couldn’t. I hate that I couldn’t.’

‘It’s okay.’ He regretted it, too, but any disappointment was completely overcome by one stunning reality:

He had a grandson.

He went searching for his wife, who was in the library with Olivia.

He and Cynthia held each other for a moment. Wonders never ceasing, joy without boundary.

She kissed his cheek. ‘Have you seen him?’

‘Just.’

He embraced Olivia, nearly speechless.

‘We just realized we’re grannies!’ said Olivia.

Cynthia wore a mildly dazed look. ‘I’m a granny! It seems only a couple of years ago I had acne.’

She and Olivia held hands and jumped around in a ragged circle.

‘Oops,’ said Cynthia. ‘I forgot I can’t jump around anymore.’

Olivia burst into laughter. ‘Me, either!’

‘I’m so happy to be your granny,’ said the person squatting down. ‘You could call me Granny Cynthy or maybe Granny C.’

‘I already got a granny.’ He had to tell people this because he could see they didn’t know.

‘And now you have two more,’ said the mom. ‘It’s okay to have more than one granny. I promise.’

What would the new grannies do? His old granny had watched TV all day and all night with a lot of screaming and killing people. He hated screaming and killing people. His old granny made him eat his cereal dry and wear diapers till he was three. He had not liked anything about his granny, but he would not tell this to anyone ever. If she heard he had said something bad, she would come and scratch his eyes out. That’s what she said she would do if he didn’t shape up. He did not want his eyes scratched out; he wanted to see everything about his new life—for as long as it lasted.

Everybody was squatting down to talk to him. So he squatted down, too.

He really wanted to see the dad again; he was starting to forget what the dad looked like except for red hai

r. His real mom had red hair; he remembered that now.

A tall girl named Rebecca Jane squatted down and introduced herself and shook his hand. ‘We are not real cousins,’ she said. ‘We’re, like, faux cousins. Like, fake. But I think we should take cousins any way we can get ’em. I have a tree house I’m too old to play in if you’d like to come over and use it.’

‘Jack Tyler! Look at you all dressed up. I’m Doc Owen. Great to have you on th’ place.’

He looked way up at Doc Owen, who had big hands and a big voice and did not squat down. ‘Just call me Uncle Doc. We’ll go for a tractor ride when you get settled in, how about it?’

‘Oh, looky here!’ said Violet Flower. ‘If you’re not cute, ain’t nobody cute. I don’t suppose you’d stand up an’ give me some sugar?’

He shook his head no and squeezed Roo really tight.

‘Come,’ said the mom, and took his hand.

‘That was a circus,’ said the mom.

They went to a door off the porch and she opened the door and they went inside. There were two beds. One big and one little. A window was open; it was cool and dark in here. A table with a radio and stuff. And some clothes hanging and some shelves really high up with blankets and more stuff.

‘This will be your bed tonight,’ she said. ‘You will sleep with . . .’ They had talked at length with the counselor about this. They could wait and see what Jack Tyler decided to call them, or they could go ahead and set the standard themselves. They had no way of knowing whether this would work into what the counselors called a ‘forever relationship,’ but that’s what she and Dooley wanted and believed in and were praying for, so why wait?

‘You’ll sleep with your dad.’

He nodded, dazed. It was like TV and not real. All the smells, the people shaking his hand and acting glad to see him, the dogs lying on the porch not going ballistic . . .

She sat on the side of the big bed and he sat on the side of the little bed.

‘Tomorrow your dad and I are getting married. Do you know what that is?’

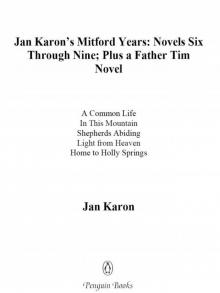

A Light in the Window

A Light in the Window Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good

Somewhere Safe With Somebody Good In This Mountain

In This Mountain In the Company of Others

In the Company of Others Come Rain or Come Shine

Come Rain or Come Shine To Be Where You Are

To Be Where You Are These High, Green Hills

These High, Green Hills Light From Heaven

Light From Heaven A New Song

A New Song Home to Holly Springs

Home to Holly Springs The Mitford Bedside Companion

The Mitford Bedside Companion At Home in Mitford

At Home in Mitford Shepherds Abiding

Shepherds Abiding Out to Canaan

Out to Canaan A Common Life: The Wedding Story

A Common Life: The Wedding Story Jan Karon's Mitford Years

Jan Karon's Mitford Years